Today, October 15th is National Pregnancy and Infant Loss Day.

I'm lighting a candle alongside so many of you for all the children in my life who could have been.

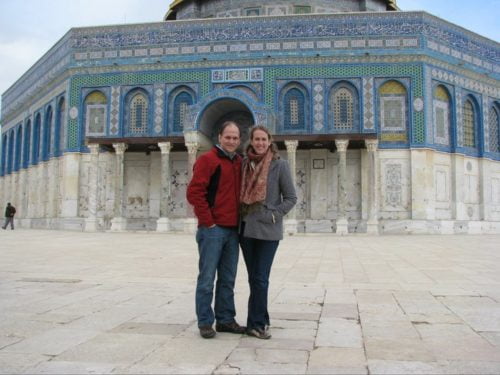

In the deepest points of my pain of child loss and infertility in 2011, I found myself on a plane headed toward Israel on an interfaith pilgrimage.

In the deepest points of my pain of child loss and infertility in 2011, I found myself on a plane headed toward Israel on an interfaith pilgrimage.

On the day we visited the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, the following is the prayer called "I am a Mother" and laid between the cracks in the wall.

Though my grief is not as raw or even present in the same way that it was back then, I am still so thankful for every time I read this prayer I published in my book, Birthed: Finding Grace Through Infertility. For it reminds me that God begins to heals us (though nothing about our situation many change externally), I believe when we're able to truly say what is on our hearts.

Here's my Wailing Wall prayer-

I am a Mother. Yet in my house there are no stray toys rolling around on the floor. There are no sippy cups with apple juice residue piled up by the sink. There are no schedules of what child goes where and when on our refrigerator.

There are no school papers stacked on our kitchen table or science project parts strewn across our countertops. I am not identified in any communities of mothers. I am not invited to forums of mothers who work outside the home.

I’ve never read What to Expect When You Are Expecting, or gone to a play group with girlfriends and their kids. I cringe when I am asked by strangers: “How many kids do you have?” Why? Because I always have to say, “I have none.”

Rather, my home life is as adult-centered as it comes. Almost never do you find my husband and me sitting at the kitchen table at mealtimes. You wouldn’t find child-protective devices on our electrical outlets or wine cabinet doors, nor do we sketch out our weekend activities around nap times or soccer games. And there are empty rooms in our home, two of them. Though we’ve planned big, it is still just the two of us. But, I am a Mother. I have children. But no one sees them.

There are those who have dwelled within me, but decided to take a short, in fact very short, stay. And I wouldn’t have known about them either, except for the signs that pointed to their dwelling. My body spoke of them through exhaustion, nausea, and cravings of unusual foods. Something new had found its way into me, and my heart counted the days and yearned for them to stay, even—just even—for one more day. I loved them, each one of them. And when they were gone, making their way out of me like a disgruntled houseguest, I wept. I cried tears so big they ran from my cheeks to my navel.

They poured like an upstream river out of my being. I didn’t know when or if the intense pain would ever stop. I couldn’t believe that such a good gift could be so cruelly taken so soon. Yet, these children were never gone from my heart. I was still their Mother. Yet, there remain in this time and space children of mine who I do not mother alone. Some have blonde hair, some have dark skin; some are very young, and others are much older than me in years but alone in their own way.

Each is searching for spaces in this crazy world to call their own and for someone to recognize who they really are. They cry out and, even though my own pain sings a loud song, I do hear them. It is my honor to see them. I fiercely want to protect them from any more of life’s deepest pains. I love them and weep for them too—not because their life has gone from me, rather because it has come and stayed close. They have come into my heart and they are now part of me too. Our bond is undeniably good.

So, no, I may never be able to attend the innocence of the average baby shower with other mothers-to-be, or be invited to a mother’s support group, or even be able to talk fully about my mothering pain and joy in public.

I am learning to accept that the gift of mothering I have been given may never be understood by most. And I might never know what physical life coming from my womb is like. Such is the cost of unconventional motherhood: loneliness.

I am learning to accept that the gift of mothering I have been given may never be understood by most. And I might never know what physical life coming from my womb is like. Such is the cost of unconventional motherhood: loneliness.

Yet, no matter how I feel or what others say or even what the future may hold for me, there is one thing I know: I am, and will always be, a mother.

If you'd like to read more, check out Birthed here.

Know if days like this are sad for you, my heart is with you. You are not alone.

One of the deepest heartaches for any parent is the loss of a child. No matter if the child was a grown adult, a school aged student or a still-born infant . . . I would even add to this list that there's also great pain in the loss of a child who did not make it out of the womb. Failed fertility treatments leave deep wounds of "What could have been." (With nothing to show for it except drained bank accounts!)

As hearts ache, it seems everything in our world says, "Just move on. Get over it."

But I'm a firm believer in lament.

We can't move on if we don't speak our truth before God first.

Some of the best lamenting is done in communities where the grieving can know they're not alone.

For this reason and may more, today I'm offering a prayer I wrote that is meant to be a resource in congregations to honor children both that are a part of communities and those who have been lost. October is National Infant and Pregnancy Loss month and I'm glad to participate in it. I hope your congregation will too.

______

Congregational Prayer in Remembrance of National Pregnancy and Infant Loss Month

God, today we want to thank you for the children who are a part of our community.

For the children that fill our community with laughter, with song and with questions

For the children that teach us in this over scheduled world how to play, how to walk slower, and curiously take in the world’s wonder.

For the children that try our patience one minute but embrace us with joy the next

We say thank you.

But, God for all the children we see and celebrate, we know there are many who we do not.

For the children who filled their parents’ hope muscles with more joy than they ever thought was possible but whose cells did not grow and multiply fast enough.

For the children with names were already spoken aloud and lived in their mother’s wombs 6 weeks, 8 weeks or even just 12 but not any longer.

For the children whose life span could be counted in hours or days but not years.

For the children who were held but whose futures are empty.

We say thank you, God, with tears in our eyes.

For it’s true, our hearts ache for all the moments of what could have been. Our pillows fill with tears of dreams dashed. Our souls overflow with loss beyond what we thought we could bear. But still, today, we want to stop and say thank you God for these children. We acknowledge them. We claim them. And we pray for peace for them and us.

Keep teaching us to welcome all your children in our community of faith.

AMEN

And there were shepherds living out in the fields nearby, keeping watch over their flocks by night. An angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. But the angel said to them, “Do not be afraid. I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find the baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”Suddenly a great company of the heavenly host appeared with the angel, praising God and saying, “Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.” Luke 2:8-14

I used to think that finding peace was impossible as a bereaved mom. In the months after Ethan’s birth and death, the devastating reality of all that I had lost could burst in on me anywhere. It might happen as I walked past a pregnant woman with a beautiful round belly on the street, or when I accidently turned down the wrong aisle in the grocery store and found myself surrounded by baby bottles and tiny terrycloth bibs, or when I opened the mailbox to find a store flier filled with rosy-cheeked infants. The world was full of reminders that I had been a mother and that my child was gone forever.

In the months after my son was born and died, I had to stop listening to the news on the radio or reading the newspaper. Nearly every story seemed to lead back to the shattered heart of a mother whose child had been killed, gone missing, been deported, gotten locked up in jail, or done something so terrible that it could never be undone. I could feel the grief of these other mothers as if it lived in my own chest. It took my breath away, knocked me off my feet, left me weeping over my breakfast or my computer screen.

Even now, four years later, moments of grief catch me by surprise, leaving me breathless with the fierceness of my longing for my missing son. But slowly, as the years have gone by, I have learned this: One of the gifts of loving Ethan is the gift of a troubled heart.

The peace that the angels announced at Jesus’ birth was not the peace of a calm and untroubled soul. It was shalom – the peace that comes when a whole community flourishes, when everyone has enough, when no mother is torn unnecessarily from her child, when no child begins life in dire circumstances. It is the peace of a community that is ruled with a kind of justice that takes the needs of everyone into account. It’s a peace that can be measured by the well-being of the most vulnerable members of a community.

Ethan was one of the most vulnerable human beings you could possibly imagine – a newborn who was disfigured and disabled, who never cried or even took a breath. His tiny body was broken beyond repair, his brain was incapable of gaining consciousness. There was nothing that could be done for him except to love him as he was.

And loving him cracked my heart wide open. Everywhere I go, I see children like Ethan – vulnerable and beautiful, gifts from God. And everywhere I go, I see moms like me – filled with a fierce unquenchable love for the children they have carried in their wombs, in their arms, in their hearts.

I see them now, and I cannot forget them – the mom who pulled into our church parking lot to wait out an immigration checkpoint with her toddler, the mom from my neighborhood who has watched her beautiful teenage boy get entangled with a gang and locked up in jail, the mom who just turned 80 and has no one to care for her disabled daughter when she is gone, the pregnant mom whose husband’s mental illness keeps them on the run from city to city without a roof over their heads or enough to eat.

It is not an accident that the sign of the arrival of God’s reign of peace was a newborn infant born in a livestock barn to peasant parents who would shortly become refugees. At the heart of this story of peace are the little ones whose lives crack our hearts wide open, leaving us troubled and longing for the day when God’s reign of peace will reach every corner of creation and provide a safe and sheltered space for the most vulnerable among us to flourish.

Let us pray:

Come, Lord Jesus, and trouble our hearts with a longing for your reign of peace. Amen.

Dayna is a member of Durham Mennonite Church (Mennonite Church USA) and part of the Rutba House new monastic community. She and her husband Eric live in the Walltown neighborhood of Durham, NC and are parents of one living son, Noah. Their firstborn son, Ethan, was born and died in 2009. Dayna is hoping this Advent for a heart open to God’s longings for the most vulnerable among us.

[If you missed Dayna's first post on "Waiting with Hope" check it out here]

When Elizabeth heard Mary’s greeting, the baby leaped in her womb, and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit. In a loud voice she exclaimed: “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the child you will bear! But why am I so favored, that the mother of my Lord should come to me? As soon as the sound of your greeting reached my ears, the baby in my womb leaped for joy. Blessed is she who has believed that the Lord would fulfill his promises to her!

Luke 1:41- 45

The story of God’s redemption is full of babies - longed for babies, unexpected babies, babies born to women long past the age of fertility, babies that no one could ever have predicted. These babies are almost always a source of delight and joy. Their births are a sign to their parents and their community of God’s presence among them, making something out of nothing. Over and over again God creates ex nihilo – out of nothing – in the wombs of Israel’s women.

And yet, the lives of these babies are not charmed – or even protected – in the ways we would hope or expect. John the Baptist, who leapt in Elizabeth’s womb in response to Mary’s greeting, grew up to be a prophet who was imprisoned and then beheaded by Herod. Jesus’ birth forced Mary and Joseph to become refugees in Egypt. His life ended with torture and execution, while his mother looked on helplessly. Many of the boys born at the same time as these cousins were slaughtered by Herod before their second birthdays.

It’s a story filled with joy, but also a story of some of the deepest pain imaginable, a story almost too horrible in places to tell. It’s a story of desperate parents, of shattering grief, of empty arms. Each of those lives was a gift, a delight, a blessing, a sign of God’s miraculous power to breathe life into human flesh over and over again. And yet, each child was radically vulnerable to the life-crushing powers of suffering and death.

Soon after my husband and I learned that the baby we were expecting had a fatal birth defect (See Dec 6 Post), I discovered a website devoted to telling the stories of families who had welcomed a child with a poor prenatal diagnosis (BeNotAfraid.net). The diagnoses and stories of these families were all different – some children fared far better than expected, while others died before or shortly after birth. Some have thrived and flourished, while others live with disabilities that cause them pain or that will eventually take their lives. But the thread that ran through all the stories was the joy these parents found in their children’s lives. Despite the pain of loving a child with a severe disability, every parent was deeply grateful for the gift of their child’s life.

It seemed very strange to find joy in the life of a child who was not yet born and already dying. How could the life of a dying child be a sign of God’s presence and blessing? How could a child whose body was so profoundly disfigured and disabled be a gift from God? How could we find joy in welcoming a child who would never gain consciousness?

Over the remaining months of my pregnancy with Ethan, I learned this: in order to receive the joy of Ethan’s life, of being his parents, we had to open ourselves to the grief of lamenting his loss. The deeper the joy we took in his life, the deeper the pain of losing him. The more we embraced the hard work of grieving his coming loss, the more we were able to receive the gifts of being his parents and taking joy in his life.

Knowing that his life would be short caused us to slow down and pay attention in ways that we might otherwise never have done. My husband and I spent time each day listening to our son’s heartbeat on a fetal Doppler. We read to him and sang to him and told him the story of our love for him. Even as I grieved, I paused to enjoy my son’s kicks and thumps inside my womb.

What I learned from welcoming Ethan into my life is this: joy is different from happiness. Joy can see and celebrate what is a gift from God in the midst of what is almost unbearable. Joy doesn’t deny or overlook what is painful and grief-filled, but it refuses to let the pain cancel out what is good and beautiful. Joy insists that God is present even in the midst of darkness and death.

Let us pray:

Come Lord Jesus. Give us the strength to welcome your life-giving presence in the midst of darkness and grief. Amen.

Dayna is a member of Durham Mennonite Church (Mennonite Church USA) and part of the Rutba House new monastic community. She and her husband Eric live in the Walltown neighborhood of Durham, NC and are parents of one living son, Noah. Their firstborn son, Ethan, was born and died in 2009. Dayna is hoping this Advent for a heart open to God’s longings for the most vulnerable among us.

Oh, that you would rend the heavens and come down,

that the mountains would tremble before you!

2 As when fire sets twigs ablaze

and causes water to boil,

come down to make your name known to your enemies

and cause the nations to quake before you!

3 For when you did awesome things that we did not expect,

you came down, and the mountains trembled before you.

4 Since ancient times no one has heard,

no ear has perceived,

no eye has seen any God besides you,

who acts on behalf of those who wait for him.

5 You come to the help of those who gladly do right,

who remember your ways. Isaiah 64:1-5

I imagined life would look drastically different today. Today (give or take a couple of weeks) was to be the day I would become a mother. I anticipated relating to Mary during the beginning of Advent—after all, I, too, would be “great with child.” Instead my arms and uterus are empty. My daughter, Avelyn Grace, died after 11 weeks in the womb.

O that you would tear open the heavens and come down . . .

After Avelyn, I was sent to a doctor who recommended a blood test. I tested positive for two strains of MTHFR, a blood mutation that can cause clots, blocking the way for nutrition to get to a developing child. I began a regimen of extra vitamins and baby aspirin. Assured that I was now armed against the dangers of MTHFR, we welcomed a second pregnancy. Seven weeks later, we had a scare. Our child was measuring a week behind with a heartbeat of 110 (slow for a developing child). The doctor was cautiously optimistic, suggesting that maybe our dates were wrong and the heart was newly developing. I’d come back in two weeks (the soonest the receptionist was able to schedule me), and we’d track what was happening.

Waiting. We often view Advent as an exciting time. We picture children barely able to contain their joy as they anticipate family and presents. Their joy becomes symbolic of our own hope as we wait for the coming Savior.

My wait was neither hopeful nor joyful. When a friend asked how I was doing, I responded the only way I knew how—that I was in hell. Was I carrying life or death? I went through the motions—taking my cocktail of pills, monitoring what I ate, attempting physical activity despite first trimester exhaustion—all the things that a woman is supposed to do while pregnant; but I knew that none of these actions could protect my child.

A week later, I called the doctor’s office, begging for an earlier appointment. I couldn’t go another week not knowing. I was asked to come in that day. The ultrasound confirmed what I already knew in my heart: our baby—Benjamin Charles—had not grown, and he no longer had a heartbeat.

O that you would tear open the heavens and come down . . .

As I’ve reflected on Advent, I’ve realized that those long generations waiting on the coming Messiah were not overjoyed in their anticipation—they were desperate. From those at the time of Isaiah, uprooted from home in the Babylonian exile, to those contemporaries of Mary, living under the rule of Rome, the people of God were reaching to grasp hope out of their extreme need.

Today I find myself empty. I find myself begging God to tear open the heavens again . . . surely then our pain would be healed. Surely then life would make sense. Surely then God would right all that seems so desperately wrong.

This year waiting during Advent means clinging to the hope of Immanuel—God with us. If God is with us, then God is here holding me, comforting me. God is breaking through the heavens to reach me, to reach all of us.

Let us pray:

O God who breaks through the heavens, let us see you even in grief. Strengthen our grip on hope when it threatens to fail. Be ever with us, Immanuel. Amen.

Jennifer Harris Dault and her husband, Allyn, live in downtown St. Louis, MO with their two cats, Sassy and Cleo. She is a member and occasional minister at St. Louis Mennonite Fellowship. She works among the Methodists as a church administrator and serves as a freelance writer, editor, and supply preacher. You can find her online at http://jenniferharrisdault.com This Advent, Jennifer hopes on behalf of those who cannot

Jennifer Harris Dault and her husband, Allyn, live in downtown St. Louis, MO with their two cats, Sassy and Cleo. She is a member and occasional minister at St. Louis Mennonite Fellowship. She works among the Methodists as a church administrator and serves as a freelance writer, editor, and supply preacher. You can find her online at http://jenniferharrisdault.com This Advent, Jennifer hopes on behalf of those who cannot

"I am confident of this: I will see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living." Psalm 27:13

I’ve waited for the labor pains to push a child out of me four times. My firstborn, a girl, slid into our arms on a frosty February morning. We had no idea that four days later, we would sit across from a cardiologist as he delivered the devastating news that her heart had stopped beating for 30 minutes that morning.

We’ve become intimate with waiting. Waiting by our daughter’s bassinet, barely able to think clearly enough to groan to God, “Please don’t let her die.” We waited for her body to recover enough to undergo surgery; we waited through 12 hours of extremely risky surgery, unsure whether hoping for the best would hurt more than bracing for the worst. We waited six long weeks before we finally took her home. She had survived, but not without tremendous losses. A brain injury damaged her gross and fine motor skills, leaving her with severe cerebral palsy and seizures.

The next eight years, we loved her the best we could, clinging to hope of seeing good in the land of the living even as we braced ourselves to lose her. We celebrated each tiny accomplishment and tried to enjoy each good moment in the midst of the survival mode we found ourselves in.

Waiting is a mind game. Spiritually, it’s a heart game too. I’ve learned that it takes constant vigilance to keep myself from getting too far ahead. Left unchecked, waiting becomes a chance to concoct elaborate worst-case scenarios so that I can attempt to control the outcome by preparing for every horrible outcome I can imagine.

I’ve lost count of how many times these scenarios left me sobbing and puffy, usually at the wheel or in bed late at night. Eventually, hopefully before I’m utterly distraught, I remember that I’m upset over a what-if, not over truth.

These many years of waiting have taught me a really important thing about what-ifs: What-ifs are not true. When I catch myself thinking things like “What if she dies?” or “What if the surgery fails?” or “What if he’s disabled like his sister?” I am not thinking on what is true. Philippians 4:8 tells us “Finally brothers, whatever is true… think on these things.”

What should I think on instead? A favorite during times of waiting, especially when things look bad, is Psalm 27:13 – “I will see the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.” In the land of the living – no matter how desperate and dark these days get, I will see goodness in this life.

Life has been very dark for us. Our daughter died early on a Sunday morning in October 2008, just 15 months after our fourth child, a boy, was born with similar heart defects. He is much healthier than she was, but the years between his diagnosis at the 18-week ultrasound and the “all clear for now” from his cardiologist were terrifying, exhausting, and tearful. But all that worst-case scenario thinking I did in my quiet moments did nothing for me when the worst did happen. God’s grace in the form of peace and the love of friends and family flooded in right at the moments when we needed help the most. No amount of anticipating can compare.

Today, we are in a new season of waiting. This advent, the fifth since our daughter died, I find myself longing to see her, but not in the body that trapped her in this life. I look forward to seeing her healed and whole, rejoicing in the presence of God. I continue to resist thinking about the what-ifs, replacing them with God’s truth, as we watch and wait to see how our son will grow and what he will need in the future.

Let us pray:

Father God, thank you for promising that we will see goodness in this life. Help me to find peace and comfort in what is true. Help me to remember that you will be with me in the waiting and even in the worst that could happen. Amen.

Joy lives in Ohio with her husband, three surviving children, a cat, and a dog. She grew up non-denominational, attended a Baptist college, spent several years in ministry in Baptist churches, and now attends a Presbyterian church. She writes regularly about her musings on life and faith at “Joy in the Journey." This advent, Joy hopes to dive more deeply into the liturgy of waiting and thus experience more clearly the joy of Jesus' birth.

Joy lives in Ohio with her husband, three surviving children, a cat, and a dog. She grew up non-denominational, attended a Baptist college, spent several years in ministry in Baptist churches, and now attends a Presbyterian church. She writes regularly about her musings on life and faith at “Joy in the Journey." This advent, Joy hopes to dive more deeply into the liturgy of waiting and thus experience more clearly the joy of Jesus' birth.

Then will the eyes of the blind be opened

And the ears of the deaf unstopped.

Then will the lame leap like a deer,

And the mute tongue shout for joy. Isaiah 35:5 – 6

What does it mean to hope for a child whose prognosis is hopeless?

At our 20-week ultrasound appointment, my husband and I learned that our first-born son had a fatal birth defect. Somewhere in his earliest development, something had gone drastically wrong. Among other disabilities, his spine and skull had failed to close, leaving his brain tissue to be washed away by amniotic fluid rather than forming the intricate folds and connections that would allow him to see and hear and laugh and run. He would never gain consciousness and, without a functioning brain, his life would be very short. On that sunny May day, our doctors were gentle but firm: There was absolutely nothing that could be done – no surgery, no intervention, no treatment – that could save our son’s life. If he did not die before birth, he would die soon afterward. There was no hope.

We had waited for Ethan for a long time, through a whole year of early morning temperature readings and fertility charting, of monthly hopes and monthly disappointments.

The winter he was conceived we were studying the stories of the Sarah, Rachel and Rebekah in our Bible study group. Three generations of women all waited with this same longing, this same fear, this same hope.

The promise of God to create a people out of no people hung on the slender thread of a longed-for but unlikely pregnancy, generation after generation. Nothing they could do, or that we could do, could bring life into an empty womb. Only God could bring life out of barrenness.

When we realized that, finally, we were expecting a child, we knew his life was a gift from God, miraculous and undeserved. But now, our longed-for child, the one whose nursery we’d already planned, the one whose name we had already chosen, the one we had waited and prayed to welcome, was going to die.

I did hope for Ethan in those months of waiting for his birth. I hoped that he knew, in whatever way he could know, that he was deeply loved and cherished. I hoped that he was not in pain and that he would be spared suffering in his birth and death. I hoped to see him with my own eyes while he was still alive. I hoped that our friends and family would see his life as precious too. Those hopes were fulfilled on the day of his birth, as Ethan slipped into life and, two hours later, into death, surrounded by those who loved him.

But my gratitude for the fulfillment of those hopes did not take away the searing pain of all the hopes that would never be fulfilled.

One of the first Sundays after Ethan’s birth and death, I stood in church next to my husband as our congregation sang a song based on Isaiah 35: “Through you the blind will see, through you the mute will sing, through you the dead will rise…” we sang. Tears ran down my face.

What I heard in those words was a wild, unbelievable promise for my boy – that his beautiful feet would yet dance, and that his blue eyes would one day see, that his tiny red mouth would laugh and sing. It’s a promise as implausible as the promise that Sarah would conceive in her old age or that Mary’s baby would free her people from oppression for all time. It’s a promise for everyone who, like Ethan, is at a dead end, whose life is hopeless. Without the life-giving touch of God, there will be no life. But with God’s life-giving breath, anything is possible.

The promise and longing of Advent is that we wait for the day when every hopeless, barren dead-end in all creation will be filled with the breath of life. We wait for the day when we will feel a leaping within us, like the baby in Elizabeth’s womb, and know that it is the Holy Spirit, filling the creation with new life. These days of waiting are not unlike the days of my pregnancy with Ethan, as we grieve with shattered hearts for what will not yet be, and long together for what God has yet to breathe into being.

Let us pray:

Come, Lord Jesus, and breath your breath of life into all our hopeless, barren dead-ends. Fill us with the quickening of your Spirit. Amen.

Dayna is a member of Durham Mennonite Church (Mennonite Church USA) and part of the Rutba House new monastic community. She and her husband Eric live in the Walltown neighborhood of Durham, NC and are parents of one living son, Noah. Their firstborn son, Ethan, was born and died in 2009. Dayna is hoping this Advent for a heart open to God’s longings for the most vulnerable among us.